I will forever think of the early 2000’s as a magical time. Along with Aaron Rosenblum and John Shaw, I was involved in the organization of more shows than I can possibly remember. Between our two student groups at Hampshire College and the volunteer work we did at Flywheel in Easthampton, Mass., we managed to book shows for what is, in retrospect, an amazing cavalcade of weirdos: Michael Hurley, Magik Markers, K-Salvatore, MV & EE, P.G. Six, Lee Ranaldo, Idea Fire Company, Graham Lambkin, Roger Miller, Jim O’Rourke, Paul Flaherty, Wolf Eyes, Sunburned Hand of the Man, Joshua Burkett, Christina Carter, Eugene Chadbourne, Thurston Moore, Tom Carter, Double Leopards, Heather Leigh Murray, Pelt, Major Stars, Overhang Party, Dredd Foole, Joe McPhee, and many others who filled our nights with strange sounds and strange times. But unquestionably the story I’ve told the most is that of the first time we had Arthur Doyle play in the Hampshire Tavern…

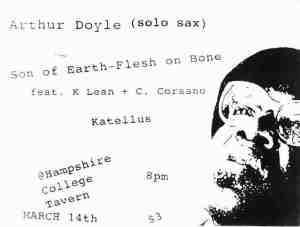

We were so excited. We designed a typically crude poster and ran through the dorms taping copies to the mirrors in every bathroom. In those halcyon days before social media, this seemed like the best way to get the word out. It hardly ever worked. (If memory serves, three people came to see Wolf Eyes.) But for whatever weird reason, the Arthur Doyle show was packed, even with our steep $3 cover.

After opening sets from Katellus (a group that eventually modulated into xo4) and Son of Earth (Aaron, John, and myself) featuring a pre-Fat Worm of Error Neil Young Cloaca and Chris Corsano, Doyle stepped up to play. I can no longer remember why, but the room was almost completely dark. He climbed up on the flimsy risers that we used to push together to form a stage, still in his bright yellow winter coat, and started his set without much fanfare.

Arthur played music that came directly out of a long, rich jazz tradition, yet was still uniquely and utterly his. His formula was pretty simple: a riff would be established on the saxophone, it would repeat endlessly, and then he would remove the horn from his mouth and sing, almost invariably along with the melody with which he’d spent so much time entrancing the listener. When he played it sounded like there were years of dirt built up in bottom of his horn, but it didn’t sound shoddy. He was loose and the songs careened from one surface cadence to another, yet there was a guiding rhythm that never abated. When he sang it seemed like he was singing only when he felt like it, but it never strayed from that rhythm of his which managed to be at once intensely personal and invitingly universal. The room, still packed for reasons I cannot quite understand, listened intently the entire time. It remains absolutely indescribable, and all the more powerful for it, really and truly something else. I had seen him play before and I would see him play again, but here he was at my school, playing for people who for the most part didn’t seem to know who he was, and there was a downright magical quality to the night.

After the show, I walked Arthur across campus back to my dorm. I’d arranged for my next-door neighbor to stay with his girlfriend so I could put Doyle in his room. I opened the door and gave the best “tour” I could of the small space I was offering him. I told him he could watch TV and mentioned that there were sodas in the mini-fridge. His eyes widened. “There’s soda in there?!?” he said, “I’ve been waitin’ allllll day! Rightrightrightrightright.” He ended the majority of his sentences in this way, with these “rightrightrightrightright”s, in this friendly way that made any of the potential intimidation wrought by his not inconsiderable legend melt away. I was no longer talking to the person who’d played on Milford Graves’ Babi, the person who’d lent such force to Noah Howard’s The Black Ark, the person who’d reached such unpredictably amazing heights with The Blue Humans, not even the person who’d thrown most of my brain out of my 19-year-old head when I’d heard his Alabama Feeling album. In person he was Arthur, right in front of you and happy to be there. I left him to it and went off to bed.

A few hours later, I awoke to the shrieks of the fire alarm. “Shit! Arthur’s smoking in the room!” I thought as I leapt from my bed and darted into the hallway. I looked to my right and saw Arthur, one foot in the hall and the other in the room, frantically looking around. He saw me and his eyes lit up. “Is this a fire drill?!?” he wondered almost joyfully. We suited up and headed out into the chilly night. I will never forget the confused looks on my fellow students’ faces as Arthur weaved throughout the crowd asking over and over, “Where the fire trucks at?”

I learned later that someone had pulled the alarm in another hall, setting off alarms throughout the building. Arthur’s illicit smoking was not responsible for the incident, and I am a prude for ever thinking that it had. In the morning I went to rouse him, only to find he’d already made his way to the dining commons, leaving four empty cans of Coke neatly placed in the dorm room trash can, each full of unobtrusive cigarette ash.

Aaron, John, and I were enrolled that semester in a class called “The Nature and Practice of Improvisation,” taught by Margo Edwards, who had studied under Cecil Taylor and been a member of The Pyramids once upon a time. Margot nurtured a deep, abiding love of free music, and had agreed to let Arthur Doyle run the class that day. After a brief introduction, Arthur stepped up in the front of the recital hall and launched into what remains, without question, the most enchanted and surreal academic experience of my life.

We had given him little more than the course title in terms of prep, but that didn’t really matter. He looked out across the classroom, composed primarily of white students, and proclaimed in his inimitable southern drawl that his music was about learning how to ad lib, and most white people do not know how to ad lib. He paused and considered his own statement for a second, then rectified it by saying that Paul Bley was actually someone who knew how to ad lib. None of this was a put down, it wasn’t dismissive, it came off more like a statement of purpose, a promise that he was about to do his best to help the class learn how to ad lib. Think about your life for a second. Think about what doesn’t make sense. Don’t you want to know how to ad lib?

He demonstrated some diaphragm exercises in case any of the horn players in the room (there were maybe two) wanted to improve their lung capacity, and after that he gave the greatest music lesson I’ve ever seen. He drew a staff up on the chalkboard and wrote out a melody. “See, you could play this, I guess,” humming the melody he’d transcribed. “You could even improvise off it.”

He then shuffled to the other side of the board and wrote the following:

YO YOO > HAO

UUP

TE

“Now this is what I’ve been working on for thirty years, rightrightrightrightright,” he chuckled. I recognized that what he’d written was the text from the cover of Alabama Feeling, but judging from the gobsmacked faces of my fellow students, I may have been the only one. Doyle had thus far been an eccentric presence, sure, but now he had suddenly shot off into the stratosphere, well beyond the realm of what anyone could possibly have expected of a person we had described only as a “jazz legend who played with Gladys Knight.”

Arthur picked up his horn and played the melody he’d written out.

“See, there’s that,” he said.

“But here’s what I’m working on,” and proceeded to play “YO YOO > HAO UUP TE” through his saxophone with chilling accuracy. He pulled the horn from his mouth with a wry smile and a “Rightrightrightrightrightright.” To this day I have never seen anything like it. Talk about school.

Arthur’s next move was to lead the class in a large-scale group improvisation. There was an electric bass, I’m sure someone played piano, Jeremy Starpoli had his trombone, and there was probably a drummer, but I can no longer remember the actual instrumental makeup of the class. John, Aaron, and I had brought recorders and sticks, so we banged chairs and made the weirdest sounds we could. Many of the students in the class seemed baffled. I neither blame nor pity them, but I do know that what Arthur Doyle brought to that class was exactly what a class about improvising needs: a potent dose of unpredictability. Looking back, the best part about Arthur’s visit was that after a certain point no one really knew what was going on (including those of us who “got it”). Somewhere in all of this I remember the incredible rush of realizing that I was actually playing with Arthur Doyle!

Arthur would pick up his horn and blare away, cutting through the cacophony of the rest of the room with such ease that it was enough to stop you in your tracks. Margo played her flute directly to him, and he’d play back. A number of times he took off his sax and set it down, listening to the sounds of the class. He looked at his watch a lot, since he had a train to catch, but he kept re-joining the group, screeching out when the energy started to lag. Looking back, those were his real moments of teaching. For someone who seemed like perhaps he was about to keel over when he spoke, he could play with an energy absolutely unmatched by any of the twenty-somethings in the room.

Eventually it was time to get to the train, so Aaron walked up and helped Arthur get his stuff together. The class played on, and never in all my days will I forget the sight of Aaron trudging out of the room, with gear and luggage in his hands, while Arthur Doyle followed behind, wearing a huge smile and sunglasses, waving goodbye with both hands.

And that was just the first time we had him play at Hampshire!

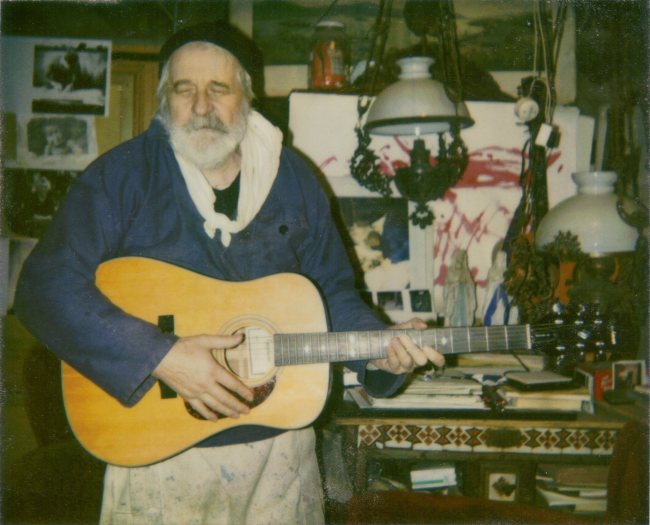

Arthur Doyle was unassuming in his presence and required little in the way of attention, but when he played or sang or spoke he commanded the room. He almost seemed like he was from another planet, but at the same time he was so completely human and so oddly in tune with what was happening in any given place at any given time. He was amazing. I am so glad I got to meet him, so honored to host him twice, and so thankful that I get to tell the story I just wrote down to anyone who hasn’t heard it.

Arthur Doyle is dead. Long live Arthur Doyle!